Note: This article was written to increase developer awareness to different attack vectors, not as a how-to for attacking existing systems.

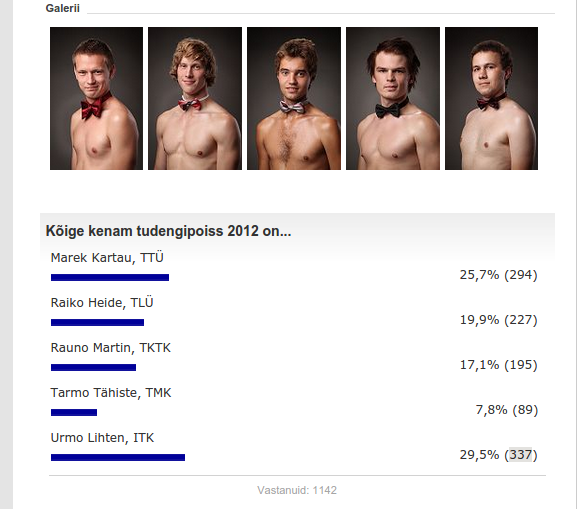

In 2012 delfi.ee (an Estonian media outlet) organized a “Hot male student” competition. Visitors of the website could cast their votes to five candidates of different universities. The code was poorly written and so the winner of the competition wasn’t necessarily the best looking candidate, but the one who had the support of tech-savvy fellow students.

Online voting systems are often implemented with naive security considerations. “Why would anyone ever delete their cookies?”, thinks the blue-eyed developer who identifies visitors by cookies. I’ll tell you why: because they can.

Think about how people could exploit your system and be the person in the team who’s most enthusiastic about tearing apart your own code. You ship the code to the real world - don’t assume all visitors will play nice with the system.

Attack vectors to online voting systems

Below is a list of different vulnerabilities most commonly found in voting implementations.

Plain refresh

The website displays a voting area. The user presses “submit” and is shown a thank-you message. The website saves no information about the vote being processed, not to its own database, not into the browser.

Vulnerability: No checks whatsoever

The website has no idea whether the visitor has already voted, hence the voting form is shown and processed for each request.

Attack: Repeat the request

No special knowlege is needed to attack this system. You can refresh the browser and vote again (spam F5) or write a short script to automate it, just sending curl requests from bash.

Forget the cookiejar

The website sets a special cookie into the visitors browser to mark the user as ‘you have voted’. This is the most common strategy for letting visitors vote only once. The server trusts the visitors browser to store the ‘already voted’ flag.

Vulnerability: Trusting user input

User input should never be trusted. Everything sent by the user to the server can be tampered with, especially if the only check is the presence of a cookie.

Attack: Forget the cookie

It is trivial for a user to remove the cookie from his browser or to write a script that just doesn’t save and return cookies.

IP based memory

The server saves the voters IP into a database of IPs who have voted. Before processing the vote, the visitors IP is checked against this database and if a match is found, an error is shown (you have already voted).

Vulnerability: Failing to identify voters

The assumption here is that IP equals person. This is not the case:

- Many internet connections are set up with a dynamic IP

- A person has more than one devices (phone, laptop, tablet)

- Visiting different hotspots (coffees) yields different WAN IPs

- VPNs provide different IPs

- Oftentimes, several devices share a single external IP

Attack: Use different IPs

Take your laptop and visit twenty different coffee shops: you don’t even have to sit down, just connect from outside the coffee house, agree to the ToS, open the browser, vote, disconnect and move to the next coffee (hint: automate).

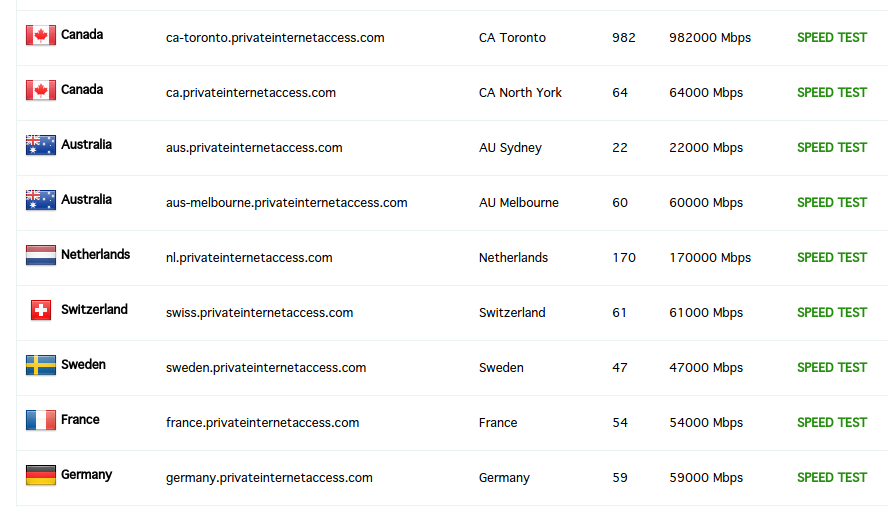

Sign up for a VPN service such as Private Internet Access or install Tor. You’ll get access to dozens of different IPs.

Request forgery

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks are a type of injection, in which malicious scripts are injected into otherwise benign and trusted web sites

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) is an attack that forces an end user to execute unwanted actions on a web application in which they’re currently authenticated

The voting page has a javascript injection vulnerability or does not implement CSRF checks.

Vulnerability: Failure to protect against XSS and CSRF

The site does not filter user input for javascript injection and accepts requests to internal endpoints from external sources.

Attack: XSS and CSRF

Try to inject javascript into the voting page itself (comments section) or do it to another popular page (either under your control or with XSS vulnerability). The malicious JavaScript would make a XHR request to the voting page and vote on the unsuspecting visitors behalf. The recent Chinese DDoS to GitHub is an example of a similar approach: unsuspecting visitors actually performed requests to an external site.

Defense strategies

There is no magic bullet that works for every use case. How you protect your system depends on your needs. Requiring all voters to be signed in with their ID card guarantees that everyone votes exactly once, but will lower poll participation rate drastically. Oftentimes it’s just a compromise on ‘reasonable’ level of protection.

Here are some things you can do.

Store state

Don’t allow multiple votes from the same source. Select a good enough authentication scheme (“how do I identify a unique user?”) and don’t allow the same source to vote twice.

Use dynamic values for submission

If your voting system has a voteId (the ID of the current poll) and selectionId (the choice that the user wants to vote for), don’t make their values easily guessable and/or static.

https://example.com/article/124/poll/submit?voteId=32&selectionId=option2

Using static values enables the attacker to just copy them into their attack script.

Either use rolling codes (dynamic, unique voteId and selectionId) for each page rendering or include an invisible form field with a dynamic, unique value (a nonce) which is verified on form submit by the server.

This technique can be defeated with web scraping: the attacker would first request the poll page HTML and then submit the vote with the unique token parsed out of the original response and into the vote request.

Require authentication

Require your voters to log in before voting. This loses the anonymity of the poll - you will get less results -, but increases the certainty that the results won’t be tampered with. A user can only vote once, since the state is tied with his user account. The effectiveness of this approach is dependant on your new user signup policy: how difficult is it for a bot to create a new, temporary, fake account?

Protect against XSS and CSRF

Filter user input for XSS. Implement same-origin policy and protect against CSRF.

Add a Turing test

Add a CAPTCHA to the vote submission. This will annoy legitimate users, but will cause problems to attackers. This method of protection is not bulletproof, but will probably deter many script kiddies.

Don’t trust user input

Never store state on the user’s browser. Don’t use cookies to mark that the user has voted.

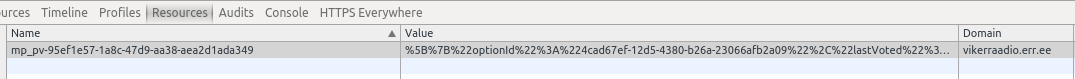

vikerraadio.err.ee stores the voter information in a cookie:

URL decoding the value of the cookie gives this:

[{"optionId":"4cad67ef-12d5-4380-b26a-23066afb2a09","lastVoted":"2015-04-19T10:30:10.050Z"}]

We can see that the cookie contains the vote timestamp and option value. What might happen if I delete this cookie? Can I vote again?

Implement IP blacklist

Compare voter IP against a database of known VPN providers. This will reduce the amount of requests that can come in from a proxy-IP, but is a dangerous ground to tread on: discrimination of privacy-aware individuals can blow up in your face. You’re basically saying that since the visitor values their privacy, they can not use your site.

Identifying automated votes

Let’s say that an attacker writes a script that makes 100 requests to the target voting server and adds 100 votes to his preferred option. As the developer of the system, how do you distinguish fake votes from the real ones?

Look at the request content

A script kiddie might be ‘clever’ enough to write a PHP script, but does he actually understand how HTTP or the library he’s using works? For example, the User-Agent HTTP header of a popular PHP HTTP client library Guzzle looks like this:

Guzzle/<Guzzle_Version> curl/<curl_version> PHP/<PHP_VERSION>

while Chrome typically sends something like this:

Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/42.0.2311.90 Safari/537.36

This information is sent to the server and can be stored in logs. The server might automatically reject suspicious requests based on the request headers or notify administrators.

Timing

So you want your script to add 100 votes? Will you send 100 requests as quickly as possible or will you space them out evenly inside 24 hours? As with the request contents, it’s easy to identify requests by their arrival time. Seeing 100 incoming votes in the space of a few seconds raises some questions.

Practical example

This example demonstrates the adding of votes to a vulnerable system. The target system identifies voters by IP (no IP can vote twice).

The attack script adds three votes to a specific option and works as follows:

- A connection to the local Tor service is established (HTTP requests will be proxied through Tor)

- A HTTP POST request to the target voting system is sent. The system rejects the request, since the current IP has already voted

- The script requests a new IP address from Tor

- A HTTP POST request to the target voting system is sent. The system accepts the vote

Morale

Be aware that your voting implementation can be hacked - but you can make it more time-consuming if you implement elementary safeguards.